Early ManThe area of the English Riviera Geopark provides one of the longest records of Pleistocene events uneffected by glaciation, not only in Southwest England but also in Western Europe. Situated beyond the southern limits of Pleistocene glaciation in the UK, the region lay centrally in a zone across which a whole range of Pleistocene mammal species would have migrated in response to repeated climatic and environmental changes. On the fringes of Europe, the area would have been at the ultimate limit of hominid migration, thus developments here have had a resounding resonance. Significant karst development within the Marine Devonian limestones provided a profusion of suitable caves, fissures and shafts where sediments, faunal remains and artefacts have accumulated by a variety of agencies. Bone preservation, even micro faunal remains, has been aided by the alkaline conditions. Bones and artefacts from these deposits were central to the pioneering work carried out in nineteenth century and subsequent controversies about the antiquity of human beings. So for anyone who thinks that Kents Cavern is just a hole in the ground....keep reading.... "Kents Cavern is beyond doubt one of the most important sites in Britain for Palaeolithic archaeology. The extensive date range of the human activity found within the cave complex and the good dating evidence create a resource which is of international significance. Human beings were using the caves from over 350,000 years ago and there is evidence of periods of occupation throughout the Palaeolithic period, up to 10,000 years ago. The value of the caves is further enhanced by the rich diversity of animal remains, which allow us to reconstruct climatic conditions through an enormous length if time, covering several glacial and inter-glacial cycles. The access to the caves for the general public allows a very rare and valuable opportunity for a wide range of people to explore and understand a remote part of the human story. The site is designated as a scheduled monument in recognition of its value to society" English Heritage

Kents Cavern contains one of the most important Pleistocene sequences in Britain. Its evidence of Middle Pleistocene conditions is unique in the South West and the site has one of the most protracted histories of research of any British Quaternary locality. The earliest excavations by Northmore and Dean Buckland (1824 - 1825) were shallow and did not penetrate the stalagmite floor below which the majority of bone- and artefact bearing sediments occur. Work later in 1825 and in 1826, by Reverend J. McEnery, penetrated further into the cave and managed to break through the stalagmite to expose softer deposits beneath. In these sediments were found the bones of hyena and woolly rhinoceros, together with human artefacts, thus demonstrating the contemporaneity of human beings and extinct animals. Because of the views prevailing in the 1820s about the age and origin of humans and of geological phenomena, MacEnery did not reveal his findings, and his notes were only published after his death by Vivian (1856) and Pengelly (1869)

The most major excavations in the cave were conducted by William Pengelly between1865 and 1880. In contrast to previous excavators, he dug the cave painstakingly layer by layer, using a grid system to establish the three dimensional context of finds and sediments. The reports were published in both monthly and annual reports (Pengelly, 1868b, 1869, 1871, 1878). (S. Campbell, C.O. Hunt, J.D. Scourse and D.H. Keen, Quaternary of South-West England, Geological Conservation Review Series, JNCC, p. 136)

Importantly, Pengelly's excavations in the Brixham Cave in 1859 provided the first published account to demonstrate that humans had occupied the region before the extinction of the cave mammals, a fact later to be reinforced by his work in Kents Cavern (Sutcliff, 1969)

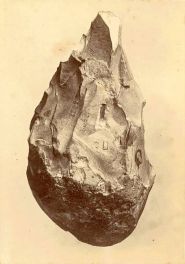

"Acceptance of the fact that people had existed alongside animals that are now extinct such as mammoth and woolly rhinoceros or those extinct from Europe such as lion, hyena and reindeer suggested a long human antiquity. Filling in the details of how people lived during these prehistoric times now inspired great interest. William Pengelly's remarkable excavations at Kents Cavern between 1865 and 1880 were a major contribution to this and Franks (appointed in 1851 by Royal Commission to establish a collection of British antiquities) did not hesitate to collect a small share of some of the oldest handaxes found at the site. Such was their importance to science that bones and artefacts were also sent to the new Natural History Museum formed out of The British Museum and opened in 1881. All of this material is still frequently examined by researchers investigating the time when people first appeared in Britain."Jill Cook, Department of Prehistory and Europe, The British Museum

Current Research Current research involves the analysis of a piece of jawbone first unearthed 80 years ago during an excavation by the Torquay Natural History Society. Originally the piece was thought to be 31,000 years old, however the current research was initiated when Dr Roger Jacobi and Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London obtained new radio-carbon dates for animal bones that were found in cave sediments directly above and below where the jaw fragment was found. These indicated that the layer in which the maxilla was found dates to between 37,000 and 40,000 years ago, and if the jawbone fragment is of a similar age it would be even more significant than first thought. If the jawbone proves to be Neanderthal, then Kents Cavern will be the only place in Britain were there is direct evidence that Neanderthals once lived, but also it would confirm that Neanderthals spread across Europe and reached Britain far earlier than is currently thought. However, a systematic exploration of the caves of Berry Head did not commence until 1983, when Peter Glanvill started an investigation that was subsequently continued by the Devon Speleological Society. As a result, today over 50 caves are now on record. This complex of coastal caves is unique in Great Britain and recent Uranium-series work on speleothem in the Berry Head caves confirms their potential for calibrating marine Pleistocene events (Proctor and Smart, 1991; Baker, 1993; Proctor, 1994; Baker and Proctor 1996). The caves provide an extreme marine environment the biodiversity of which is still being investigated. |